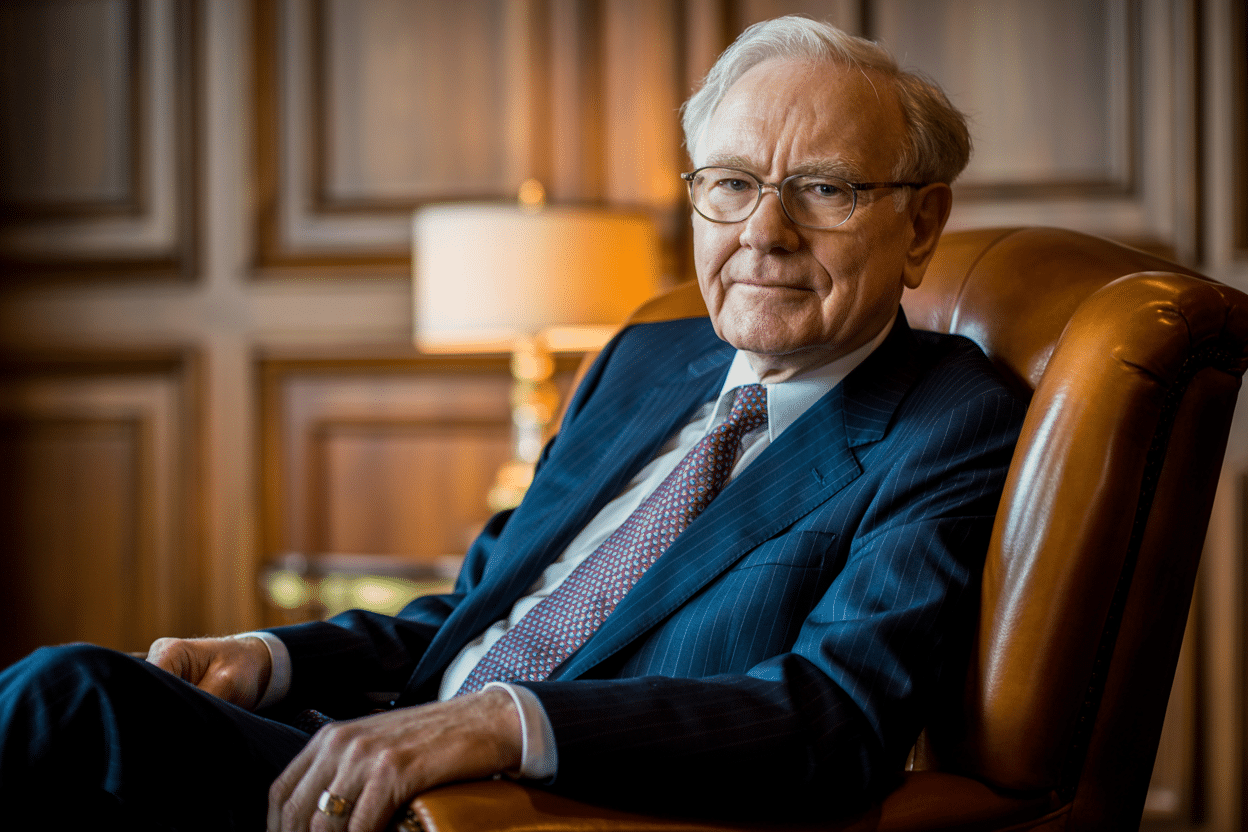

“My wife—when we got married, we ended up in Las Vegas, but I walked into this casino. It was either a Flamingo—it’s kind of a motel arrangement—and I was 21 and my bride was 19. I looked around the room, and there were all of these people, and they were better dressed than us. It was a more dignified group than perhaps currently, but they’d flown thousands of miles in some cases. They’d gone to great lengths to come out to do something that was mathematically unintelligent. They knew it was unintelligent, and I mean, they couldn’t do it fast enough in terms of rolling the dice, you know, and trying to determine whether they were hot or whatever they may be. I looked around at that group, and they knew they were doing something that was mathematically dumb, and they’d come thousands of miles to do it. I said to my wife, I’m going to get rich.” – Warren Buffett.

Warren Buffett’s investment philosophy crystallized during an unlikely moment: his honeymoon in Las Vegas. The young investor witnessed something profound that would shape his approach to wealth building for decades.

While most people see casinos as entertainment venues, Buffett recognized a fundamental truth about human nature and mathematical probability that would become the cornerstone of his investment strategy. His revelation demonstrates how rational thinking and mathematical intelligence can create extraordinary wealth by capitalizing on others’ predictable mistakes.

1. The Las Vegas Revelation: How a Casino Honeymoon Shaped Buffett’s Investment Philosophy

The moment in Las Vegas sparked Buffett’s epiphany. He turned to his wife and declared, “I’m going to get rich.” But his path to wealth wouldn’t involve gambling—it would include positioning himself on the profitable side of others’ mathematically poor decisions.

The casino experience taught him that intelligent, successful people consistently make irrational financial choices, creating opportunities for those who think clearly about probability and value. This insight became the foundation for his investment approach: profit from others’ mathematical unintelligence rather than participate.

2. Be the House, Not the Gambler: Positioning Yourself for Mathematical Advantage

Buffett learned to position himself like a casino rather than a gambler. Casinos profit because they have a mathematical edge that plays out over time, regardless of short-term fluctuations. Similarly, Buffett seeks businesses with sustainable competitive advantages that generate predictable profits over long periods.

Through Berkshire Hathaway, he operates like “the house” by owning insurance companies that collect premiums upfront and pay claims later, providing float for investments. He acquires businesses with economic moats—sustainable competitive advantages that protect them from competition.

Whether it’s Coca-Cola’s brand power, BNSF Railway’s infrastructure advantages, or Apple’s ecosystem lock-in, these companies possess mathematical edges over competitors.

The key insight is that while gamblers hope for lucky streaks, successful investors create systematic advantages. Buffett doesn’t rely on market timing or stock-picking luck. Instead, he owns pieces of businesses that have mathematical advantages in their industries, allowing him to profit consistently from their superior economics while others chase short-term market movements.

3. Mr. Market’s Emotional Mistakes Create Your Biggest Opportunities

Benjamin Graham’s Mr. Market allegory, which Buffett frequently references, illustrates how emotional decision-making creates opportunities. Mr. Market is a hypothetical business partner who offers to buy or sell his share of a business daily, with prices fluctuating wildly based on his mood rather than the business’s actual value.

When Mr. Market is depressed, he offers to sell excellent businesses at bargain prices. When euphoric, he demands premium prices for mediocre companies. Rational investors profit by buying when Mr. Market is pessimistic, selling when he’s overly optimistic, or ignoring his daily price quotes entirely.

Buffett treats the stock market as a servant, not a master. He focuses on business fundamentals while others obsess over daily price movements. This approach allowed him to purchase shares in outstanding companies during temporary market pessimism, such as buying Coca-Cola stock in the 1980s when the market undervalued the company’s global growth potential.

The mathematical unintelligence lies in letting emotions drive investment decisions rather than analyzing underlying business value.

4. Be Greedy When Others Are Fearful: Profiting from Irrational Market Behavior

Buffett’s famous maxim, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful,” captures how contrarian thinking generates wealth. Market crashes and panics create exceptional opportunities because fear drives people to make mathematically poor decisions, selling quality assets at prices far below their intrinsic value.

During the 2008 financial crisis, while others panicked about bank failures, Buffett invested billions in Goldman Sachs and Bank of America, securing favorable terms that generated substantial profits. His willingness to act when others were paralyzed by fear demonstrated how mathematical thinking trumps emotional reactions.

The psychological principle behind this strategy recognizes that humans naturally follow crowds and make decisions based on recent events rather than long-term probabilities. When markets crash, people extrapolate recent losses into the future, creating buying opportunities. Conversely, people extrapolate recent gains during bull markets, leading to overvaluation. Rational investors profit by doing the opposite of what feels natural to most people.

5. Focus on Business Fundamentals While Others Chase Market Psychology

While most investors focus on stock prices and market movements, Buffett concentrates on business economics. He evaluates companies based on their ability to generate consistent earnings, maintain high returns on equity, and operate with minimal debt. This fundamental analysis reveals a company’s actual value independent of market sentiment.

Most investors’ mathematical unintelligence lies in confusing stock prices with business value. They buy stocks because prices are rising or sell because prices are falling, without understanding the underlying businesses. Buffett profits from this confusion by purchasing shares in excellent businesses when their stock prices don’t reflect their intrinsic value.

His approach involves studying annual reports, understanding competitive advantages, and analyzing long-term business prospects. While others chase trends and react to news headlines, he focuses on timeless business principles. This patient, analytical approach creates a sustainable edge because most people can’t or won’t do the necessary research to understand what they’re buying.

6. Patience Beats Speed: Why Long-Term Thinking Is Your Competitive Edge

Buffett’s favorite holding period is “forever,” reflecting his belief that time is the friend of wonderful businesses and the enemy of mediocre ones. While most investors trade frequently, seeking quick profits, patient investors benefit from compound returns generated by quality businesses over decades.

The mathematical advantage of long-term investing stems from allowing exceptional businesses to reinvest their earnings at high rates of return. When a company consistently earns high returns on invested capital and reinvests those earnings wisely, wealth compounds exponentially over time.

Frequent trading represents mathematical unintelligence because transaction costs, taxes, and timing mistakes erode returns. Studies consistently show that patient investors outperform active traders over long periods. Buffett’s extraordinary wealth resulted not from brilliant short-term trades but from holding stakes in outstanding businesses for decades, allowing their superior economics to compound his wealth.

7. Mathematical Intelligence in Action: How Buffett Turns Others’ Mistakes Into Wealth

Buffett’s success demonstrates how mathematical thinking creates sustainable competitive advantages. He profits from others’ unintelligence by maintaining rational decision-making while others succumb to emotional biases, short-term thinking, and mathematical errors.

For individual investors, applying Buffett’s principles means focusing on businesses rather than stock prices, thinking in decades rather than quarters, and making decisions based on probability and evidence rather than emotions and hunches. His recommendation for most investors to buy low-cost index funds reflects this mathematical approach—accepting market returns while avoiding the costs and mistakes associated with active trading.

The key insight is that mathematical unintelligence isn’t limited to casinos. It permeates financial markets through emotional decision-making, short-term thinking, and misunderstanding of probability. Rational investors can systematically profit from these mistakes by maintaining discipline, focusing on fundamentals, and thinking long-term, while others make poor decisions.

Conclusion

Warren Buffett’s Las Vegas revelation illuminated a profound truth: mathematical unintelligence creates systematic opportunities for rational thinkers. By positioning himself like a casino rather than a gambler, focusing on business fundamentals rather than market psychology, and maintaining long-term perspectives while others think short-term, he transformed others’ mathematical mistakes into extraordinary wealth.

The lesson for investors is clear—rational thinking and mathematical discipline provide sustainable competitive advantages in a world where most people make predictably poor financial decisions.