In every society throughout history, people have organized themselves into social hierarchies. These structures, which we call social classes, profoundly shape our lives, determining access to resources, opportunities, and even how we view ourselves and others.

Despite our modern emphasis on individualism and meritocracy, class divisions influence everything from educational outcomes to health, relationships, and political perspectives.

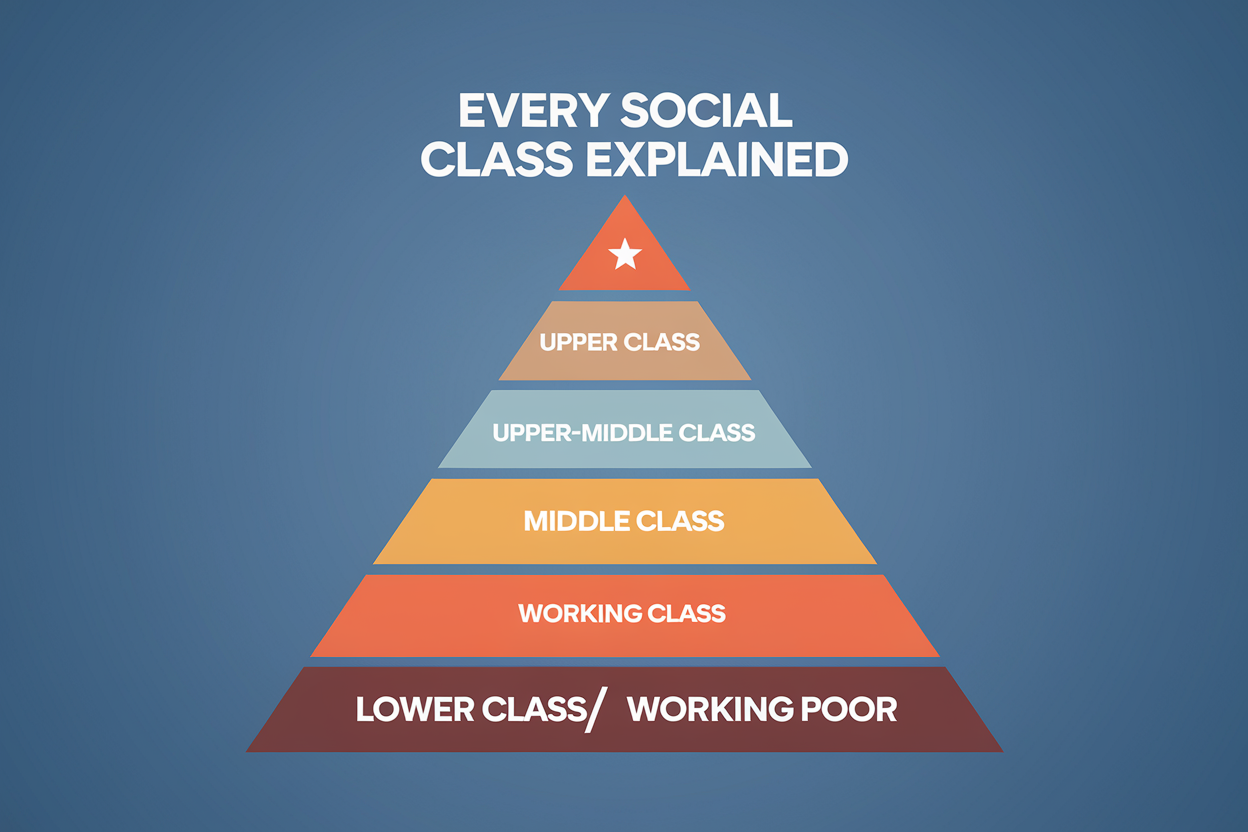

This article explores the major social classes in contemporary society, examining what defines them beyond simple income categories and how these divisions continue to evolve in our rapidly changing world.

1. Understanding Social Class in Modern Society

Social class refers to the hierarchical categorization of individuals based on their economic resources, occupation, education, and social status. While these divisions may seem straightforward, they are complex constructs shaped by history, culture, and financial systems.

Sociologists have developed various frameworks to understand class. Karl Marx viewed class through the relationship to production, dividing society into those who own the means of production and those who sell their labor. Max Weber expanded this view to include status and power alongside economic position.

Understanding class structures helps explain persistent patterns of inequality and opportunity across generations. While modern societies often emphasize meritocracy, research consistently shows that class origins significantly impact life outcomes in education, health, wealth accumulation, and longevity.

2. The Upper Class: Power and Privilege

The upper class represents a small fraction of society, typically estimated at 1-2% of the population in most developed countries. This elite group possesses substantial wealth, often accumulated across generations through inheritance, investments, and high-value business ownership.

What distinguishes the upper class isn’t merely wealth but the power and influence accompanying it. Members frequently attend prestigious educational institutions, occupy leadership positions in major corporations, and maintain extensive networks that provide access to exclusive opportunities.

The upper class differs from other social strata in its relationship to work—many derive income primarily from investments rather than salaries. This financial independence creates freedom from constraints that affect other classes. Preserving wealth across generations remains a defining characteristic, with careful attention to estate planning and strategic alliances that consolidate resources.

3. Upper-Middle Class: Professional Excellence

The upper-middle class comprises highly educated professionals, successful business owners, and senior managers who enjoy comfortable financial security without reaching the upper class’s extraordinary wealth. This group typically possesses advanced professional degrees from respected institutions.

What characterizes this class is its strong emphasis on educational achievement and professional credentials. Members frequently invest heavily in education for themselves and their children, viewing it as essential for maintaining status.

The upper-middle class typically values cultural capital alongside economic resources, often engaging with arts, international travel, and other markers of sophistication. While not immune to economic downturns, this group possesses sufficient financial buffers to weather most crises without fundamental threats to their lifestyle or status.

4. Middle Class: The Backbone of Society

The middle class encompasses many occupations, from office workers and teachers to small business owners and skilled technicians. This diverse group typically has some post-secondary education and enjoys reasonable economic stability, though with significantly less cushion than upper-class groups.

What defines the middle class isn’t just income but specific life patterns: homeownership aspirations, investment in education, retirement planning, and moderate consumption habits. Middle-class families often organize their lives around long-term financial goals.

In recent decades, the middle class has faced increasing economic pressures from rising housing, healthcare, and education costs and relatively stagnant wage growth in many occupations. Despite these pressures, middle-class identity remains powerful in many societies, associated with values of hard work, responsibility, and modest aspiration.

5. Working Class: The Skilled Workforce

The working class encompasses individuals in skilled manual labor, service work, and clerical positions that typically require some training but not extensive formal education. This includes factory workers, construction trades, retail staff, and service industry employees.

What distinguishes working-class occupations is their relationship to physical labor or direct service to customers. These occupations often have structured work hours, limited autonomy, and compensation through hourly wages rather than salaries.

Working-class economic security has become increasingly vulnerable to economic shifts, technological change, and globalization. Many jobs that previously provided stable middle-class lifestyles have been replaced by positions offering less security. Despite these challenges, working-class communities often maintain strong social bonds and distinctive cultural practices.

6. Lower Class and Working Poor: Facing Economic Challenges

The lower class and working poor face persistent economic insecurity despite active participation in the workforce. This group includes individuals in minimum wage positions, part-time employment, seasonal work, and the gig economy, often working multiple jobs to meet basic needs.

What characterizes this class is the precarious nature of their economic situation—limited financial reserves, vulnerability to unexpected expenses, and difficulty accessing essential services. Many experience periodic financial crises from medical emergencies or job losses that can trigger hardships.

Despite full-time work or working multiple jobs, many struggle with insufficient income to meet basic needs, creating chronic stress and difficult trade-offs between necessities. The working poor frequently face the contradiction of labor-intensive lives with limited economic reward or security, challenging simplistic narratives about the relationship between work and prosperity.

7. The Underclass: Systemic Disadvantage

The underclass refers to populations experiencing persistent, multi-generational poverty. This group faces substantial economic participation and mobility barriers, often concentrated in communities with limited resources and opportunities.

What distinguishes the underclass is not simply low income but structural disconnection from mainstream economic and social institutions. Factors contributing to this disconnection include limited educational opportunities, inadequate housing, geographic isolation from employment centers, and insufficient support systems.

Many experience intersecting disadvantages related to geography and other factors that compound economic challenges. The concept highlights how poverty can persist when multiple systems fail to provide adequate pathways to opportunity.

8. How Social Class Shapes Opportunity

Social class profoundly influences life opportunities from birth through adulthood. Class position affects access to quality education, creating divergent paths that often reproduce class status across generations.

Healthcare access and outcomes show transparent gradients across class lines, with lower socioeconomic groups experiencing higher rates of chronic disease and more limited access to preventive care.

Beyond tangible resources, class shapes social networks and the information, support, and opportunities they provide. Cultural capital—familiarity with dominant social codes, communication styles, and expectations—similarly varies by class background and influences how individuals navigate institutions from schools to workplaces.

Class intersects with other social identities, including race, gender, and geography, to create unique patterns of advantage and disadvantage. Understanding these intersections helps explain why simplistic views of merit and opportunity fail to account for persistent patterns of inequality.

9. Beyond Economic Divisions: Alternative Views on Class

While economic resources remain fundamental to class analysis, contemporary sociologists recognize that class encompasses cultural and social dimensions. Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital posits that knowledge, tastes, and social practices, often acquired unconsciously through family and social background, act as markers of class position and can be leveraged for social and economic advantages.

Status-based approaches examine how prestige and social honor operate alongside economic divisions. New frameworks recognize emerging class formations in digital economies, where traditional boundaries between owners and workers become blurred through platform models and remote work.

The complexity of modern class structures challenges simplistic hierarchical models. Many individuals occupy contradictory class positions—highly educated professionals with significant cultural capital but limited economic resources or entrepreneurs with substantial wealth but limited formal education. These complexities suggest class remains powerful while continuously evolving.

Conclusion

Social class remains a fundamental lens for understanding how societies allocate resources, opportunities, and rewards. While specific boundaries between classes may blur, the fundamental reality of stratification persists across societies.

The complex interplay between economic resources, cultural practices, social networks, and institutional access creates distinctive life experiences beyond simple income categories. Class influences everything from health outcomes to political perspectives while intersecting with other social identities to develop unique combinations of privilege and disadvantage.

Recognizing these patterns doesn’t mean accepting them as inevitable. Many societies continuously debate and adjust policies addressing class inequalities through education, taxation, labor protections, and social support. Understanding the multidimensional nature of class can inform more effective approaches to creating societies where opportunity is more equally distributed.